I finished up the most confusing novel last night. It was quite possibly the oddest mismatch of style and subject matter I have ever read.

The person who wrote it was funny--very, very funny. The book, however, was about a horrible apocalypse.

So, first there was kind of a tone mismatch--you know, joke, joke, joke, horrible death, joke. It was jarring, and not in the good way--I actually like the ha-ha-ha-ha-oh-my-God! thing, which is part of why I like Joss Whedon--but this felt more like a comedy routine that got interrupted by someone in the audience having a heart attack.

Eventually--and I think this is a testament to how good this person is at writing humor--the horrible apocalypse became funny. It was very dark humor, to be sure, but definitely effective humor. After a point, however, the horrible apocalypse became so horrible that the writer couldn't make jokes about it any more.

That's when things really started to drag. Part of it is that I simply don't find awful tales of complete horribleness all that interesting. Part of it was just the loss of the humor, which was really delightful and keenly missed. But part of it was that I honestly don't think the writer was particularly interested in writing that part of the story. The prose got muddled, so that it was a lot harder to figure out what was actually going on. The action churned to a halt.

It was frustrating, because this writer is clearly extremely talented. The book would have been so much better had it been about...gee, pretty much anything else. Any humorous and satirical topic would have worked so much better with the humorous and satirical prose style. It was like reading a novelization of 28 Days Later written by Jane Austin or Christopher Buckley or Terry Pratchett.

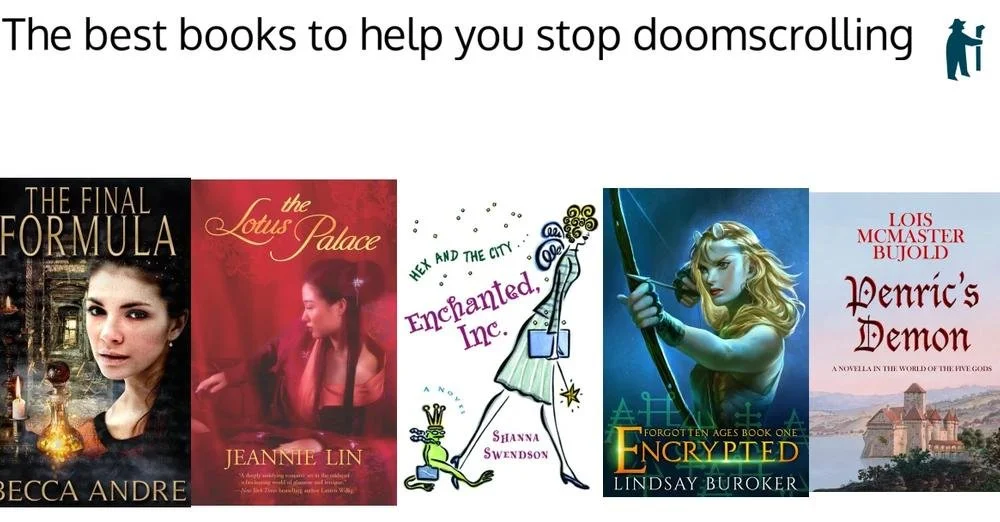

It's not just this one book. Lindsay Buroker talks about figuring out what your "unfair advantage" is and exploiting it. I think that's a huge challenge for writers, because let's face it, we're waaaay too close to our work.

In addition:

1. We may love a genre we just don't write very well. This author clearly loves apocalyptic movies and even name-checks a bunch of them. But you know something? Those movies tend not to be funny, and this person is really, really good at funny. I see the same thing happen when people who write well at one length keep trying to force themselves to write at another.

2. We may write something very well that conventional wisdom says people don't want to read. So many people bitch and bitch about long, descriptive passages because they were forced to read Lord of the Flies in high school and HATED it. But you take a book like Wool, and one of its great joys is the brilliantly-written long, descriptive passages. Imagine how much poorer that book would be if Hugh Howey had decided to follow the advice I've seen a million places and cut all that "crap" in order to get right to the action.

3. Our strengths can be our weaknesses. Do you know how many literate adults I know who read the first Harry Potter book, thought, Meh, and never read another? Many, many, many. I keep trying to explain to them, No, you must read the entire series because J.K. Rowling's big strength is her complex plotting across all seven novels. But of course the first book doesn't have a complex plot--it's quite simple. People who read it and stop can never understand why someone like me--an adult with a fancy-pants literature degree--is so impressed by that series.

Or take Trang. What do people compliment? The characters. What do people complain about? The fact that it takes a while to get to the "action." Except that the "action" in that book is the character arc--it's not really a book about aliens and portals; it's a character-driven story about a man who is undergoing a significant life crisis. Philippe Trang freaking out at a party on Earth is actually really important to the story--just not the story about space aliens.

So, should I not write sci-fi? Maybe not--it's hard to know. Which is kind of my point....