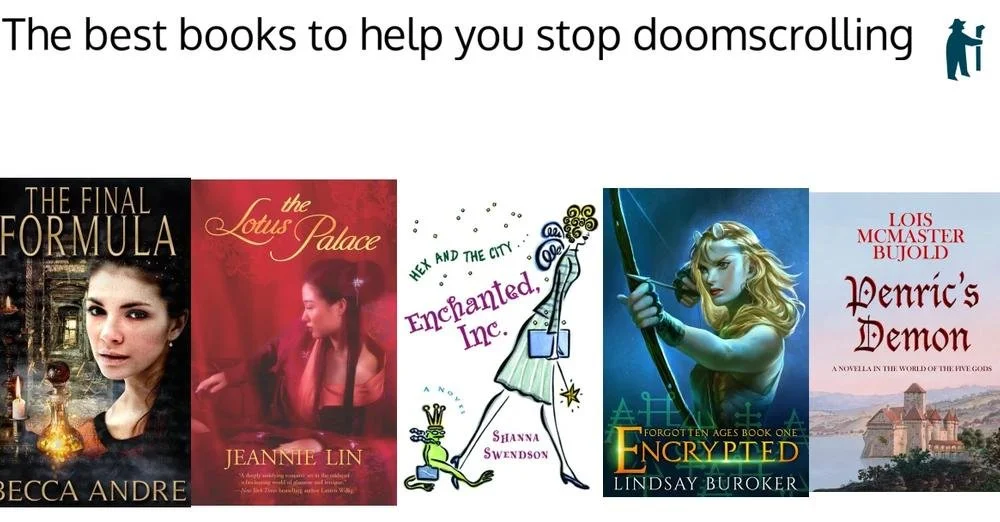

I put together some recommendations for Shepherd: Best Books To Help You Stop Doomscrolling. Enjoy!

books

Dreyer's English

Since I got my second shingles shot yesterday, I’m not good for much today, so I thought I’d read a book my sister got me for my birthday: Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style.

It reminds me a lot of Eats, Shoots & Leaves in that it’s waaaaaay more readable than one of the classic style guides or a grammar textbook while managing to cover a lot of very important information about how grammar works (including an entire section on ghost rules! yay!).

But I think there’s one aspect that less-experienced writers might find confusing. As you may have gathered from the subtitle, the book isn’t really intended to be the final word on anything.

The problem in my mind stems from the fact that Dreyer will sometimes posit his pet preferences as the “correct” (or more accurately, standard) way. They are not. If he’s noting that, hey, all the style guides disagree with him, but they’re wrong, you need to realize that he is espousing something that is not standard.

It’s fine if you want to use what Dreyer thinks ought to be standard English—maybe you agree with him that Dreyer’s English is better than regular English! But if you’re trying to convince a reader that you actually do know how to drive a bus, then you’re much better off using one of those standard style books he occasionally disagrees with.

Fantasy, race & romance

Via Isobel Carr, there’s an interesting article up about how race is used in the fantasy genre, and how that might be improved.

I’ve read a couple of fantasy/science-fiction romances that I felt were a little…weird this way. The way that they work is that the Protagonist is secretly an X. Then they meet Romantic Object…who is also an X! This means that they are soul mates who will bond and marry and live happily ever after, the end.

I mean, I know I’m a hard sell on romance, but I can’t be the only one to think this is lazy as shit. Why bother trying to generate chemistry between two characters when you can just make them both, I dunno, androids or empaths or Greek gods or aliens from the plant Blorn! Easy-peasy!

Except it’s not very engaging, and it’s got this weird, forced, essentialist element to it. I mean, if I’m from Blorn, and you’re from Blorn…there are probably a billion or so other Blornians back on our home planet, so what makes our relationship so damned special? Maybe we feel a connection because we are two lonely Blornians on Earth, but it’s going to take a bit more than that for our relationship to move past the hot fling stage into love eternal.

Progress report

I've been away, but I'm back and wrote 1,180 words! Whoot! And some exciting words they were!

You know, I've mentioned that I'm a tough sell with romance books, but I've been really enjoying the ones by Amy Raby (be aware that they are fairly erotic). I think it's because she does a really good job of fitting the romances into some pretty complex fantasy/adventure plots. Often when I've tried adventure romances, it feels like there's this We Must Save the Universe! story going on, and then it gets interrupted by, Will Our Heroine be Able To Find Love? which winds up making the romance feel extremely trivial. (You're never going to find romance if you're all blown to kingdom come!) But with these stories the geopolitics going on actually affect the main characters in personal ways, so resolving the one helps resolve the other and makes it all very gratifying. I like 'em!

I got my last shot/You get a free book

Last allergy shot was yesterday! Yay! Now I'm back on the once-a-month schedule, thank the Lord.

And my sister's book is free for the next five days! Check it out!!

Go, sis!

My sister has taken the plunge and self-published a novella! It's called The Brother on My Back, and it's a Sherlock Holmes story (he's in the public domain)--but Sherlock is, like, 14, and it's set in the 1990s. Let's say there was considerable debate over whether or not she should just rename the character, but a lot of the storylines are related to the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories, so she felt she could not in good conscience.

It's on Amazon, and she will be doing a five-day free giveaway starting Thursday, so give it a whirl, and if you like it, please review it! If you really like it, she's got others--I think three are basically written.

The POV Games

I'll probably start writing again tomorrow, but in the meantime I've been watching the movie versions of the Hunger Games books, which has been pretty interesting from a writing standpoint. (Spoilers ahead!!!)

I really liked the book The Hunger Games a lot, but I found Catching Fire and Mockingjay to be very disappointing, in no small part because they were very repetitive. ("Let's play the Hunger Games--again!") I haven't watched the two Mockingjay movies yet, so perhaps I'll be let down, but I have seen the movie versions of The Hunger Games and Catching Fire.

And I was really surpised by how good they were. With The Hunger Games I was surprised by how much the movie improved on what I thought was a very good book; with Catching Fire I was equally surprised by how much the movie improved what I thought was a tiresome and unoriginal book.

What made the difference? Getting the hell out of Katniss' head.

I realize that Katniss' voice is a big part of what made the series so popular with teenagers, and it's not like she doesn't have reason to be bitter and whiny, but bitter and whiny is what she is--the adults in her life suck, and she has to take on all this responsibility if she wants her family to survive. Being a teenager, she does so with as little grace as is possible, and she makes zero effort to understand the people around her--in her eyes, they're all just jerks and oppressors.

That's not a huge problem with The Hunger Games book, but it is part of what makes the movie stronger: The gamemaker, who Katniss just sees as a heavy, is revealed in the movie to actually be a naive idealist, which was to me much more interesting.

Her limited viewpoint becomes more of a problem in the Catching Fire book because Katniss knows less. In The Hunger Games, there are actually two games going on at the same time: The overt game where you kill everyone else off, and the PR game where you win viewers' hearts. Katniss knows about the second game, and she plays it very well--which is why both she and Peeta survive.

In Catching Fire the second game is political revolution, and Katniss knows nothing about it. Her scope of vision is limited to survival, and her experience is limited as well--in her mind, the second Hunger Games isn't meaningfully different than the first.

Of course, it's entirely different, and the movie makes that evident much earlier. You see President Snow's political calculations, and you know that the decision to put Katniss in the Hunger Games again isn't just another lousy thing to fall upon her out of the blue, which is all it is to her. (Adults suck, man!)

And honestly, I had much more sympathy for her tunnel vision in the movie, because I wasn't trapped in it for the duration like I was in the book. At the end of both the book and the movie, Katniss is shocked to hear that, in response to the revolution, her home district has been destroyed. In the book, that annoyed the piss out of me--she's been afraid of something like that happening the whole time, she's been blathering on about it at length, over and over again. Why is she surprised? In the movie, her bafflement at the speed at which events have unfolded is simply more understandable--she is just a kid, after all.

Oh, so interesting

I'm back from my trip--still getting settled back in and readjusting to Pacific Standard Time.

I've been catching up on the Wall Street Journal, and there is a fascinating review of a biography of Robert Heinlein in it. The really interesting bit is that the reviewer puts their finger on something about Heinlein that I think is really true: His early books are much more political/persuasive (I am of the school that feels they can be propaganda-ish and annoying), but his later books are just kind of meaningless.

From the review:

The novels for adults that followed were just as emotionally compelling. And that's exactly the problem. "Starship Troopers" is about a future society facing a total war against an implacably hostile alien species: Heinlein does not just describe the war with his typical vividness; he conjures up a high-tech military culture, with a worldview and ruling ideology to fit (among other things, only veterans have the right to vote), and hurls the reader into its midst with such imaginative force that its rationale seems not only inevitable but somehow desirable. Many readers have been deeply moved (I know of more than one enlistment in the real-world military inspired by it); others have felt that they're being bullied by a brilliant piece of fascist propaganda. Five decades on, it remains the most bitterly divisive book in the history of sci-fi.

Heinlein himself was greatly upset by the controversy. He wrote that he had no idea whether the militaristic society in the book would really work. . . . And when, in 1974, the young Vietnam veteran Joe Haldeman published a direct attack on the politics of "Starship Troopers" in his own sci-fi novel "The Forever War," Heinlein repeatedly went out of his way to praise it.

Heinlein grew to be just as ambivalent about his other masterworks. "The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress" is a visionary epic of a lunar colony breaking free from earth's government and establishing an anarchist-libertarian utopia. But even as it was being enshrined by the libertarian movement as a foundational text (it was endorsed by Milton Friedman), Heinlein turned cagey and evasive about whether he was advocating its revolutionary agenda. Once again, it was as though his own persuasiveness was making him uncomfortable. This discomfort escalated exponentially into nightmare with "Stranger in a Strange Land." Heinlein always insisted that he meant it as nothing more than a satirical and ironic fantasy à la "Candide" (the working title was "The Man From Mars"); he was both amused and appalled when the hippies took it up, enchanted by his luxuriantly sybaritic portrait of a Martian free-love commune. . . . But he was horrified to discover that the novel was the bible of the Manson cult.

I don't think it's entirely a coincidence that the catastrophic fall-off in Heinlein's work began after the 1969 Manson murders. The novels he wrote in the 1970s and 1980s wholly lack his old persuasiveness. Nothing in them is real, nothing is at stake and nobody takes anything seriously. . . . The overall effect is so low-energy and stupefying that it's hard to believe it isn't somehow deliberate—as though Heinlein is out to repudiate his greatest talent and make sure no reader is inspired to take any action whatever.

That really does kind of sum up Heinlein, right? More generally, you can never know how people are going to take a piece of science fiction, especially one that engages with political ideas. Firefly, for example, is sometimes touted by libertarians as depicting a sort of paradise--you know, the kind of paradise where slavery exists and where you have to ready a firearm before you answer a knock at the door.

Certain jobs are REALLY not stories

The HVAC guy took forever yesterday (verdict: the furnace can be saved; the heat pump, not so much), so I wound up reading a bad novel by a writer who is famous, but not for novels. (Which means that all the jacket blurbs were these atrocious, ass-kissy, "What a masterful genius!!!! I only hope you write more of your WONDERFUL novels (and give me a job!)"-type things. I was like, Dear God, don't encourage this crap.)

One of the WONDERFUL aspects of the novel, showing the author's masterful genius!!!, was that the actual plot did not begin until fully a third of the way into the book. Instead, the entire first third of the book was dedicated to describing the day-to-day life of . . . a professional writer.

Not just any professional writer--a professional writer who doesn't write novels (but would like to write one), and who is about the same age and lives in the same area and is the same gender as the actual author. (Yeah, he really dug deep into his imagination for that one. I'm gonna assume that the resentful ex-wife and adult children are his, too.)

I keep reading this. Since everyone who writes a book is a writer, there are a bazillion gazillion not-particularly-imaginative books out there about, you guessed it, life as a writer.

As I've said before, someone simply doing a job is not enough to carry a book. And let's face it, writers have about the most boring jobs imaginable.

Especially established writers. This guy's not poor; he's not uneducated; he's not desperate. What does he spend an entire third of the book doing? Oh, you know, arguing with his agent, worrying about the wording of his latest contract, wondering when he'll get time to write that novel, wondering if he'll have to (shudder) teach another university class (the horror!!!) to maintain his middle-class lifestyle.

These are the kinds of thing that, when Tweeted about, get you on White Whine. Honestly, the only way the stakes of that story could have gotten any lower would have been if the guy was having lots of great sex, but not with the woman he really wanted to have sex with.

Ooops! Sorry! That was in there, too!

In a way, the book reminded me of Michael Chabon's The Wonder Boys, if The Wonder Boys had sucked instead of being awesome. Once the plot starts, the guy . . . kind of realizes that there is a world around him? But not really. The book is not, Guy Realizes That He Is a Self-Indulgent Prat so much as it is, Self-Indulgent Prat Learns To Feel Better About Himself, which . . . what are the stakes here, exactly?

Harry Potter and moral choice

One of the things I've wanted to do for some time was read the Harry Potter books all in one go. I started reading the series when it was about half out, and I just wasn't going to go stand in line at the bookstore at midnight or anything like that (I did actually buy two of the books--both in paperback at airport bookstores--but other than that I used the library), so I wound up waiting a year or two between books, at which point I'd forgotten who half the characters were. So I thought it would be worthwhile to re-read them all at once.

It's interesting how different an experience that can be. One of the things about reading Harry Potter the first time around was that I didn't know whether it was just a bunch of cute kid's stories or if it would turn out to be the plotting wonder it actually was. It's clear re-reading it that it is really just one HUGE book, and knowing that, the ups and downs are far less pronounced. I got a lot more enjoyment out of the first couple of books in the series this time around because I knew what they were setting up. Order of the Phoenix annoyed me much less this time, because although that book doesn't really have much of a plot payoff by itself, it does set up the later books. On the other hand, Goblet of Fire, while enjoyable, wasn't the absolute kick in the pants it was the first time I read it and realized that, as the character of Harry aged, the books were going to get waaaaaay more sophisticated.

I do kind of feel more ambivalent about the ending. (This is going to get VERY spoilery, so if you haven't read the books yet--hey, my sister hasn't--go do that first. Really.)

A number of people argue that Neville Longbottom is the most important character in the Harry Potter books, and I can totally see that--Neville has a great character arc, and as a writer, I think there's a lot to be said for having tertiary characters that have discrete arcs, even if we only see those arcs in glimpses. It's really intriguing to realize that something's going on elsewhere, plus it gives the reader the sense that this is a real world, not one in which all the other characters exist for the sole purpose of serving the main plot and main character. (The fact that Ron and not Harry winds up with Hermione is another example of J.K. Rowling making her world more robust and realistic, and less of a fantasy-fulfillment thing. In lesser hands, Hermione would have been the prize that Harry wins, and Ron would have accepted it because, you know, Harry's the main character.)

But I think Rowling kind of slipped up in the end, because in his final confrontation with Voldemort's snake, Neville is simply more heroic: He withstands torture, breaks a curse, summons a magical object, and without hesitation slays a powerful semi-magical creature.

Harry has also been extremely heroic, of course--he's been tortured and has actually died, on purpose, in order to defeat Voldemort. In addition, he has delved deeply into the world of wand lore and has uncovered vital knowledge that will allow him to overpower Voldemort.

But at the very end, what does he do? Harry uses a disarming charm, and Voldemort's own curse bounces back on him, killing him.

At least it's not explicitly an accident, but that's pretty weak, isn't it? If had been made explicit that this was an effect Harry could expect from a really solid disarming, I'd be OK with it, but it just seems like a bit of a cop-out, especially compared to all the other stuff Harry has both suffered and done. (And he's done quite a bit--Rowling is not shy about having Harry & Co cross lines and do things they once though shockingly immoral, which is something I really like about the book.)

The Harry Potter books are actually better than most: The whole thing where heroes have to kill the evil villain, but of course they can't just murder someone, because they're the good guys!!! is rarely handled well--more often than not, the death of the villain is explicitly accidental. That's supposed to make you think that the good guys are still good (I guess because they are unsullied by sin), but I hate it--it smacks of Pontius Pilate washing his hands to me. Heroic people--hell, just plain old decent people--do not go through life abdicating responsibility and trusting on chance to set everything straight. When the choice is between doing something unpleasant or allowing something genuinely horrible to happen, the person who preserves their precious purity by doing nothing is NOT a hero.

The one time where I saw this handled really well was in another story that is supposedly for kids but actually quite gratifying for adults: The television series (NOT the movie) Avatar: The Last Airbender. In that series the main character, Aang, is so opposed to killing that he is a vegetarian, and yet he's put in a position where he is expected to kill the main villain (who is very, very bad). What I like about it is that Aang's opposition to killing is a real choice with real consequences--the writers don't just have a rock fall out of the sky and solve Aang's problem for him--and Aang has to stand up for his choice and find an alternate solution in an environment where that is very difficult. What makes it heroic is the moral courage--Aang must take action, and he must do what's right, not just for him, but for everyone else, too. And it's a much more realistic take on what being a decent person is actually like: The stars don't magically align for you because you try to do the right thing; you have to do the right thing even when it's difficult.

Good limits, bad limits

After thoughtful consideration yesterday, I decided that the best way to deal with my story problems was to have a raging bout of insomnia that would leave me unable to so much as read a book. (Although, granted, my current book is John McPhee's Annals of the Former World. Guys, this may be the lack of sleep talking, or it may be because The New Yorker has so thoroughly adopted his prose style that I feel like I could finish his every sentence, but I am getting to be of the opinion that McPhee is overrated as a writer. At one point he lists a bunch of different geological ages because he thinks the names are kind of cool. I'm looking forward to the page where he just starts listing names out of the phone book--you know, because they're kind of cool. And his stories just never seem to climax. I get the feeling he was probably a pretty boring person.)

Anyway, today I read Kris Rusch's post on how nowadays she can write what she wants, YEAH! Screw publishers and their schedules and their little minds!

And on the one hand, I am delighted that e-books mean that short stories and novellas and little genres can flourish once again, and Rusch certainly brings up some examples of publishers being really arbitrary about stuff.

On the other hand--well, I also read this today. It's about a Web site I happen to enjoy called Eat Your Kimchi, which is by two Canadians living in Korea. Initially they started making videos about life in Korea so that their families could see what was going on with them, but then they started getting traffic from people who were curious about Korea.

And then they started getting traffic from really oversensitive Koreans who HATED them and wanted them deported! Things got extremely unpleasant, especially when they would criticize K-Pop groups, because Korean pop fans are notoriously insane.

The thing is, as awful as it got and as unfair as it certainly was, I've watched a lot of the old videos, and I have to say that their newer ones are much better. Why? It's not the production values (although those have improved), it's the fact that they no longer offer up knee-jerk negative reactions to things that they don't know anything about ("ERMAHGERD, this food has TENTACLES in it!"--uh, you've never had calamari?).

You could say that they've become more careful, but I would argue that they've become more thoughtful--and that's a good thing. It prevents them from falling into the whole Ugly American (Ugly Canadian?) rut, where they just run around shrieking, "ERMAHGERD! Why are things DIFFERENT here? It's like we're in some kind of foreign country or something!"

In addition, when they do get critical (which they still do), they are either very thoughtful about it (like this) or they come up with something hilariously funny. Remember those crazy K-Pop fans? Instead of just bitching about these lunatics who desperately need to get a life, they came up with the immortal character of Fangurilla.

The line between being true to your vision and just being self-indulgent is a fine one, and I think it's harder to draw a lot of times because 1. criticism is never pleasant, and 2. sometimes it is delivered in an entirely malicious and dishonest fashion. But even the worst form of criticism can have some value--at least if you take the right lesson from it.

The too-neat ending

I enjoyed Star Trek: Deep Space Nine when it came out, but I never actually watched it that regularly until the last season. So recently I decided to watch the whole thing.

The show's series finale is this behemoth of nine or ten linked episodes, and what I remember feeling about all that when it finally came to its conclusion was a vague sense of disappointment, a sense that it was really all too pat. Watching it again, this time with the full weight of seven seasons of the show behind it, I felt exactly the same way.

If you've never watched the show, it takes place on a space station, and the main characters are a mix of humans and aliens. In that great Star Trek/social science-fiction tradition of using aliens as metaphors for human problems, there's a lot in there about issues of identity in a multi-cultural society. (Gee, no, it didn't influence the Trang series at all--why do you ask?)

Well, at the end those issues are largely dropped in favor of basically assigning each alien back to their home planet, whether or not they have actually lived there as adults or can relate to the people there in any kind of meaningful way. There's a big dollop of wish-fulfillment thrown in there, so that no fewer than four of the major characters end up ruling and/or saving "their" people, and another gets hoovered up to live with some mystical aliens (leaving behind both a son and a pregnant wife) because he's kind of related to them in some vague, mystical fashion. The concept that someone might leave a place, move someplace new, and be happier in the new place is totally discounted--the major alien character who stays on the station does so only because his planet is no longer traditional enough for him.

While metaphor can deepen a story, I feel like the finale of Deep Space Nine shows how the sloppy use of metaphor can really weird people out. Part of the problem with the finale for me is that if you have that metaphor (alien identity = ethnic identity) in the back of your mind, you can't help but notice how neatly the conclusion of the series parallels the "solution" certain white supremacists have for the United States--just ship everybody back to where they came from, and we'll all be happier!

The other issue is that, while it's really an ensemble piece, there is a main character, the captain of the station, named Benjamin Sisko. He is pitted against a character named Dukat, who is always kind of an antagonist, but who, as the show progresses, becomes an outright villain.

The problem with Dukat is that, as he becomes a villain, he explicitly and repeatedly identifies himself as the enemy of Sisko. He makes it very clear that there is going to be--in fact, there must be--some big confrontation between him and Sisko, and that only one of the two will survive.

And then, in the series finale, there's a big confrontation between Dukat and Sisko, and only one of the two survives. Take a wild guess which one.

Ugh. You know, that kind of set-up is extremely common: The big hero meets the big villain and defeats him. It's why Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is kind of a waste of paper--870 pages to learn that Harry Potter must defeat Voldemort? I'd figured that out already, thanks.

When you're presenting something that's been done so many times before, to pull it off you either have to do it in a really interesting way (which I think the Potter books do, eventually), or mix things up a bit. One of the joys of the Buffyverse was that, more often than not, the big hero (Buffy or Angel) did not defeat the big villain. Sometimes they did, but more often than not things didn't work that way: A friend might do the dirty work, or maybe the big villain actually wasn't such a big villain and got offed by a bigger villain. If the villain was a serious threat, getting rid of him had to be a group effort, and sometimes the hero wouldn't quite manage it properly and the villain would come back later. In the case of Angel (who becomes a villain at one point), he was only a villain temporarily, so taking him down was an agonizing experience.

The point was: It was unpredictable. Things in the Buffyverse always had the potential to go sideways. As a result, even when there was a straight-up hero-defeats-villain scenario, it was fresh, because there was a very real chance it might not come off. You didn't come out of it feeling like you could have saved a lot of time by checking out on the storyline the moment Big Villain said, "Ha-ha! It's going to be a battle to the death between Big Hero and me!"

Go, Crabby!

So, Crabby McSlacker has indeed put out a book based on her Cranky Fitness blog, which I've mentioned is a favorite of mine. I just wandered over to Amazon to look at it, and holy crap, it's free right now! Even if you don't want to buy it, just go read the book description--hysterical!

What edge are you cutting?

I recently read Pricing Beauty: The Making of a Fashion Model by model/sociologist Ashley Mears. It's an interesting, if rather dryly-written, book about the economics and culture of fashion modeling. (And I was surprised reading it to realize that I know the male model "Michel"--he comes off as way more of a freak in that book than he is in real life, I think because English is not his first language. If you write nonfiction, please note how simply changing someone's name is not nearly enough to protect their identity.)

Anyway, Mears points out that there are two major schools of modeling: Commercial modeling (catalogs, advertisements) and editorial modeling (fashion shows, magazine shoots).

Commercial modeling is seen within the industry as, you know, commercial. Hot babes do well. But it's also regarded as Not Art--the idea is to appeal to Middle America, not challenge it. You or I probably have just as good an eye for a commercial model as anyone in the industry.

Editorial modeling is seen more as an art form. Those seriously bony girls with light-green, shiny skin and no eyebrows? They are editorial models. They are considered high fashion and on the cutting edge. While commercial models are pretty and sexy, editorial models are edgy, avant-garde, belle laide, and many other French terms for funny-looking. While commercial models are supposed to appeal to Middle America, editorial models are supposed to prove that whoever is trumpeting them is a true artist, with a unique and fabulous eye.

Which, as Mears points out, means that editorial models are suppose to appeal to other people in the industry.

Given how cutting-edge editorial models are supposed to be, how they are supposed to challenge conventional notions of beauty, which group do you think is more diverse?

. . . ?

Commercial models. Yuppers! People actually do market testing with commercial models, and it turns out that Middle America is actually a pretty diverse place! If you're pretty and sexy, no one cares much what your racial or ethnic background is!

Editorial models, in contrast, tend to be white, white, white. And really anorexic. (Apparently there are no really good non-white models in existence. It's kind of funny to watch the RAGE boil out of Mears' academic prose in response to that one.)

It turns out that if you have this small little gaggle of people who all socialize together and who are all constantly judging each other's taste, that taste becomes really homogenized--even if these are people who pride themselves on seeing the world differently!

I think that's a big part of why you get homogeny in movies and commercial books, too--it's not just the financial expectations that make everyone in the industry seek to produce clones of the latest hit. It's that tendency to move as a herd--everyone's in the same city, they have worked or will work together, and they do tend to socialize together. Consciously or not, they don't want to piss each other off, and that makes even their "edgy" decisions very, very safe--within their world, anyway.

How Audiobooks Work

Things have been a little chaotic here--hopefully by Wednesday everything will have settled and I'll be able to write. Anyway, I did manage to read David Byrne's How Music Works, which was interesting to me on a lot of levels.

He has an entire chapter on the many different ways to distribute music nowadays (he uses examples from his own career, breaking out expenses and revenues--he's a very open guy). That section was of special interest because while I don't mind giving Trang away as a free podcast, I'd also like to have an audiobook that people can buy if they want, plus if I record the later titles I would want to do them as paid audiobooks and not as free podcasts.

A lot of the places he was talking about just do music, because the only way onto Amazon or iTunes if you are an audiobook is via Audible, and that means going through ACX. The issue with that is that they have pretty specific production requirements--I don't know if they are impossibly specific, though, mainly because I don't know what's involved in mastering. You also have no control over price.

The other option (actually, it looks like you can do both) is Bandcamp, which is a straightforward retail arrangement--no distribution included. They charge a percentage of your sales, but other than that it's free. You can set your price there however you want, which is nice.

Serendipitously, Erin Dolan of Unclutterer, a site I often read, has produced her own audiobook. In her case, she just put an E-Junkie shopping cart onto her Web site--a click on the link takes you right to PayPal.

That looks interesting, doesn't it? For $5 a month I could sell every e-book format plus the audiobooks directly from this Web site. Well, that's going into the Must Investigate in the Future pile.

The magic of limits

Since this week has been a lost cause (I slept last night--huzzah!--but had too much scheduled to do today for writing), I've been reading a book called Lord Darcy by Randall Garrett. Lord Darcy is actually an omnibus volume containing Garrett's various stories about a guy named--you guessed it--Lord Darcy.

It was very entertaining to me as a reader, but it was also really interesting to me as a writer, because the Lord Darcy stories are probably the only truly successful marriage of the mystery genre and the science fiction/fantasy genre that I've ever read.

The problem with most other attempts at amalgamating those two genres is that mystery novels are basically puzzles--here's a dead body, let's figure out how it got there. Puzzles work because of there are limitations on the puzzle-solver, who doesn't just know all the answers but has to sort it out using only partial and often unreliable information.

Science fiction and fantasy, however, are genres where human limitations are usually greatly reduced or utterly eliminated through technology or magic. So they usually don't mix well with mystery: The wizard waves his wand or the robot taps into the database, and the problem is magically (and boringly) solved!

So limits have to be put on these things. In the Vorkosigan Saga (which is not strictly mystery, but there are occasional crimes as well as a great deal of espionage), there's a truth serum called fast-penta. But it doesn't work in everybody, some people are deathly allergic, and some people have been made deathly allergic specifically so they can't be interrogated.

Garrett handles this issue by having the magic be extremely rules-based and quite limited--it is, in the alternative history of Lord Darcy's world, scientific. Magic that would be really inconvenient in a mystery novel, like teleportation, simply doesn't exist. Instead, much of the magic revolves around the principle that things that were once whole wish to be whole again. So, for example, a forensic sorcerer (yes, that's a thing) could take blood from the scene of a crime and blood from a suspect, smear them on the opposite sides of a dish, and cast a spell. If it's the same blood, it will pool together, and you've placed your suspect at the scene.

It's very clever because it lets the investigators know some things (whose blood is that, what gun did that bullet come from) without knowing all things.

If it sounds like forensic sorcerers aren't much more useful than forensic scientists, well, they're not. And Garrett goes even further: Because magic is scientifically understood, actual science--chemistry, physics, biology--isn't understood very well at all, so technology has suffered greatly. While the books are set in the years Garrett wrote them, the technology mostly comes from the previous century. Far from magic being something that solves all problems, magic is something that has effectively created more limits.

For example, at one point Lord Darcy is secretly searching a room at night with the help of "a special device."

It was a fantastic device, a secret of His Majesty's Government. Powered by little zinc-copper couples that were the only known source of such magical power, they heated a steel wire to tremendously high temperature. The thin wire glowed white-hot, shedding a yellow-white light that was almost as bright as a gas-mantle lamp. The secret lay in the magical treatment of the steel filament. Under ordinary circumstances, the wire would burn up in a blue-white flash of fire. But, properly treated by a special spell, the wire was passivated and merely glowed with heat and light instead of burning. The hot wire was centered at the focus of a parabolic reflector, and merely by shoving forward a button with his thumb, Lord Darcy had at hand a light source equal to--and indeed far superior to--an ordinary dark lantern.

That's just so wonderful on so many levels. Not only is a plain old flashlight a source of awe (you merely have to shove forward a button with your thumb!), but it's repeatedly compared with things the reader isn't familiar with (various lamps and lanterns), because of course in Lord Darcy's world, that's what used. My most-favorite bit is the fact that they solve the major engineering puzzle of the incandescent bulb--how do you prevent the filament from just burning up?--by using magic. Of course. Because that's what they use to solve all their problems. It just doesn't work that well.

Why did he do that?

I recently finished Subversives: The FBI's War on Student Radicals, and Reagan's Rise to Power by Seth Rosenfeld. It's a fascinating non-fiction book, and I feel like it contains a valuable lesson for writers of fiction as well.

The book is about the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, and how it basically went off the rails and dedicated enormous resources to hassling hippies in the late 1960s. (They have long hair! LOOOONG HAIR!!!) Now, I knew that that had happened--I've read Steal This Book and Soul on Ice and a ton of other 1960s counterculture "classics" that to be honest are for the most part incredibly boring to the contemporary reader. (Yes. You smoked weed and got laid. That is so fascinating.)

But I'd never really gotten any insight into why it happened, other than Hoover was The Man, and The Man can't handle having his mind blown by young people smoking weed and getting laid, man! (I feel obligated to point out here that Hoover was probably gay, and some of the people he worked with quite closely for a long time were most certainly gay, so I don't think his problem was Puritanism.) Rosenfeld spent more than 20 years fighting the FBI in court for access to its files, so he has a lot of letters and memos and whatnot that provide insight into Hoover's thought process.

And a fascinating thought process it is! For starters, Hoover surrounded himself with people who thought exactly like he did--proof that the echo chamber existed long before the Internet. So by the time the late 1960s rolled around, assumptions like "Democrat = Communist" were widely accepted within the FBI, because it's not like anybody in the Bureau knew any Democrats or, God forbid, actually was one. In other words, there were no reality checks taking place, and no speed bumps on the road from Legitimate Security Threat Land to Crazy Town.

What was the legitimate security threat? Well, the Comintern was indeed a real thing, and in the 1930s and 1940s most Communist parties in the United States were actively managed by the Soviet Union and supported Soviet interests over American interests. In the late 1940s, people working for the Soviets were spying on the American atomic-weapons program. So that sort of thing was a totally legitimate area of interest for law enforcement, which is why the FBI got involved.

Unfortunately, as the level of Communist/Soviet activity in the United States waned in the 1950s and 1960s, the FBI just assumed it was better hidden. The way the Communists operated really helped stoke the paranoia--remember, this was a political movement that developed under the totalitarian regime of the czars. So Communists had a policy of 1. lying about who they were, and 2. surreptitiously taking control of organizations that were largely not Communist by having a small number of Communists enter the organization and take leadership positions.

The secrecy meant that if a group had few or no people in it who were openly Communist, you still couldn't be 100% sure that it was not a Communist front organization that would promote the interests of the Soviet Union. And indeed, Hoover and his people were, in general, 100% sure groups that were making trouble were Communist front organizations, even if the vast majority of the people in those groups were clearly not Communists.

So when the free-speech movement started at UC Berkeley in 1964, Hoover did not see a bunch of college kids agitating to pass out flyers on campus (yawn). He saw a Communist front organization (!!!). I was surprised about how sincerely Hoover believed this--I'd always assumed that the people making these sorts of allegations knew they were pretty ridiculous. But Hoover's underlings obediently produced a report saying that the FSM was a Communist front organization, and then Hoover himself was genuinely quite surprised when that report was discredited.

At this point, Hoover's thought process went like this:

Q. Why are these kids acting so weird?

A. Soviet infiltration!

Within just a couple of years, though, even the FBI knew that the Soviets had SFA to do with what was going on at Berkeley. Unfortunately, at this point they didn't care. Hoover's thought process had devolved to:

Q. Why are these kids acting so weird?

A. Who cares? They must be destroyed!

And that's when the FBI became an instrument of straight-up political oppression--hippies, peaceniks, Democrats, they were all subversives and all the enemy.

Do you see how much more interesting that kind of thing is that the simple-minded "Hoover is The Man" or "Hoover is evil" or "Hoover can't handle freaks"? It's a story, and a tragic one--a guy starts out in trying to protect people's freedom, but thanks to certain flaws in his character (an unwillingness to associate with anyone who does not agree with him; an unwillingness to adapt to change; a willingness to break the law to pursue an investigation), he winds up becoming quite possibly the most serious threat to that freedom. The slow decline in his ideals, the gradual sense that there are no rules that apply to him, the creeping belief that anyone who disagrees with him is evil--you can see how it could happen. You can relate to it even if you think you would have handled things differently.

It's so much more engaging than just having a two-dimensional villain plopped before you, along with instructions to hate him. Bad guys who are just bad--you know, one day they just decided to become evil, as you do--are such a wasted opportunity.

Lessons from a polar expedition where five people died

Yeah, I'm reading The Worst Journey in the World, a memoir written by Apsley Cherry-Garrad (God, British names crack me up sometimes) about the Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole, where Robert Falcon Scott died along with four other people after reaching the pole a month after Roald Amundsen did.

I want to say that I realize that Scott's reputation during the 20th century went from unrealistically high to unfairly low, and I'm not trying to pile on here. (Honestly, I feel like before people criticize explorers, mountain climbers, and the like for poor judgement, they should first give sleep deprivation, hypoxia, exhaustion, and malnutrition a shot for a month or two and see how their mental processes hold up.) I also feel like people who run down Scott tend to valorize Amundsen for contrast, and he was hardly a perfect person.

Still, Cherry-Garrad's book--which was not written to be critical of Scott at all--is a really frustrating read, and I think it does contain lessons for authors trying to navigate this new world of publishing. (Hey, if I'm willing to do it with the Transformers, clearly nothing is a bridge too far for me.)

Lesson 1: Admit what you don't know. Scott had visited Antarctica ten years before on an earlier expedition. You'd think that would have been helpful, right?

Oh, no. Scott felt like he knew exactly what Antarctica was supposed to be like. The ice was supposed to be this way, the blizzards were supposed to be that way, the temperatures were supposed to be another way. They were all supposed to be exactly the way they were when he had visited Antarctica before.

The Terra Nova expedition spent almost a year in Antarctica before making the disastrous run for the pole. In that time, it became painfully obvious that the weather in Antarctica is totally unpredictable. It was colder-than-expected inland. Blizzards could crop up at any time. Local weather conditions were fantastically specific, so it could be sunny and warm in one spot, and two miles away there could be a blizzard. Also, it was considerably colder than it had been at any time during the previous expedition.

Now, I am the first to admit that it's hard to plan for, This is totally unpredictable!!! But they didn't seem to try. Instead they assumed that the weather during the run for the pole would be the way Antarctic summer weather is "supposed" to be--clear and relatively warm. They left depos of food rations on the assumption that people would be able to walk about 10 miles a day, every day.

So what happened when the support parties headed back north and ran into unexpected storms that slowed them down? They went hungry. What happened when the party that actually reached the pole headed back north, were going more slowly than planned, and ran into more unexpected storms? They died--11 miles away from a huge food cache.

Let's hope no one actually starves to death here, but do you understand why it makes me nervous when people with absolutely no track record of sales make financial plans based on the expectation that they will sell X many copies of their book? This is not salaried work: You do not get a regular paycheck every two weeks. As a new writer, you don't want to set up your financial life so that if you don't sell X copies your book each and every month, you go hungry. And you really don't want to be that tragic author who perishes in the snow six months or six years before sales finally start to kick in.

Lesson 2: Leave room to fail. Cherry-Garrad makes a big deal out of the fact that Scott wasn't just making a "pole dash"--he was trying to figure out what would actually work in the Antarctic.

So, for the run to the pole, they had motor vehicles, ponies, and dogs. Before his death, Scott even arranged to have mules brought down on a relief ship so that people could try them out, too.

The problem with all this was that Scott didn't give himself any room to have an experiment fail. The motor vehicles and the ponies didn't do well, and in neither case was that some big surprise. Dogs did much better (that's what Amundsen used), but Scott didn't have many dogs because he had packed so many motor vehicles and ponies.

I feel like Scott's motivation were very noble: He was hoping that motor vehicles would provide an alternative to using and killing animals. But in 1910 the reliability of motor vehicles was just not something you could bet your life on, even if you weren't on a polar expedition--cars were still hand-cranked at that point, for God's sake.

Using ponies was also a new and untested idea. And it basically killed Scott. That huge cache of food he died 11 miles away from? It was supposed to be 30 miles further south, but the ponies couldn't make it.

So, give yourself room to fail. If you have a great new marketing idea, that's swell--don't mortgage your home. Don't set yourself up for disaster. Remember--these are experiments, not certainties.

Lesson 3: Be honest and realistic about your goals. Remember how Cherry-Garrad said that the expedition was no mere pole dash?

Unfortunately, that's not how Scott saw it: He felt like the entire worth of the expedition depended on reaching the South Pole.

The actual run to the pole was not just a disaster at the end: It was a disaster the entire way. Those unexpected storms didn't just unexpectedly turn up on the way back north, they unexpectedly showed up and unexpectedly slowed the party on the way to the pole as well. Of course rations earmarked for later in the trip unexpectedly got eaten early, because everything was unexpectedly taking so much longer.

Seeing how all their planning was proving inadequate, did they abort the run for the pole while they still could? No, they did not.

Did Amundsen? Why, yes, as a matter of fact, he did. His first shot at the pole was aborted because of bad weather. It's not that he wasn't competitive (he was), but he also seemed to understand that sheer force of will would not get him to the pole and back alive--good weather would.

Amundsen was just more realistic, and he made a ton of compromises to get himself to the pole that Scott did not. Scott put his base camp in a location that was further from the pole and actually cut off from it for part of the year (!) because it was a better location for the many scientists in his party. Amundsen, in contrast, had almost no scientists in his party. Amundsen was doing a pole dash, period.

Now obviously we can argue that Scott was a nobler person who was dedicated to the ideals of science and all that. We can argue that Scott's "failed" expedition actually accomplished more that was useful than Amundsen's "successful" one. But the problem was that Scott defined success in a certain way (reach the pole!), but he wasn't really willing to acknowledge that (this is no mere pole dash!). As a result, he was ill-situated to actually reach his goal, and then he got desperate.

Honestly, I see that most often with writers who really, really want to be popular--they want big sales! and their name in lights! and fame and fortune! But they also want to write whatever they want, whether or not that's something anybody wants to read.

You can't, OK? Even with self-publishing, we're still operating in a market. Certain types of literature are more popular than other types of literature.

If your goal is to tell Danielle Steele to suck it, your abstract poetry is not going to get you there. I would guess that most people who write bestsellers think long and hard about what most people want to read before they write--I've certainly read and heard memorable interviews with ones who did.

If you don't want to write within those sorts of constraints, that's great--neither do I. But I also never assumed the Trang books would be big commercial sellers. In fact, the whole point of writing Trang for me was to move away from making Big Macs. I'm not going to freak out and do something stupid because there isn't a McSisson's on every corner with a sign proclaiming how many billions I have served--if I wanted that, I would have written a very different book.

Writing to your strengths

I finished up the most confusing novel last night. It was quite possibly the oddest mismatch of style and subject matter I have ever read.

The person who wrote it was funny--very, very funny. The book, however, was about a horrible apocalypse.

So, first there was kind of a tone mismatch--you know, joke, joke, joke, horrible death, joke. It was jarring, and not in the good way--I actually like the ha-ha-ha-ha-oh-my-God! thing, which is part of why I like Joss Whedon--but this felt more like a comedy routine that got interrupted by someone in the audience having a heart attack.

Eventually--and I think this is a testament to how good this person is at writing humor--the horrible apocalypse became funny. It was very dark humor, to be sure, but definitely effective humor. After a point, however, the horrible apocalypse became so horrible that the writer couldn't make jokes about it any more.

That's when things really started to drag. Part of it is that I simply don't find awful tales of complete horribleness all that interesting. Part of it was just the loss of the humor, which was really delightful and keenly missed. But part of it was that I honestly don't think the writer was particularly interested in writing that part of the story. The prose got muddled, so that it was a lot harder to figure out what was actually going on. The action churned to a halt.

It was frustrating, because this writer is clearly extremely talented. The book would have been so much better had it been about...gee, pretty much anything else. Any humorous and satirical topic would have worked so much better with the humorous and satirical prose style. It was like reading a novelization of 28 Days Later written by Jane Austin or Christopher Buckley or Terry Pratchett.

It's not just this one book. Lindsay Buroker talks about figuring out what your "unfair advantage" is and exploiting it. I think that's a huge challenge for writers, because let's face it, we're waaaay too close to our work.

In addition:

1. We may love a genre we just don't write very well. This author clearly loves apocalyptic movies and even name-checks a bunch of them. But you know something? Those movies tend not to be funny, and this person is really, really good at funny. I see the same thing happen when people who write well at one length keep trying to force themselves to write at another.

2. We may write something very well that conventional wisdom says people don't want to read. So many people bitch and bitch about long, descriptive passages because they were forced to read Lord of the Flies in high school and HATED it. But you take a book like Wool, and one of its great joys is the brilliantly-written long, descriptive passages. Imagine how much poorer that book would be if Hugh Howey had decided to follow the advice I've seen a million places and cut all that "crap" in order to get right to the action.

3. Our strengths can be our weaknesses. Do you know how many literate adults I know who read the first Harry Potter book, thought, Meh, and never read another? Many, many, many. I keep trying to explain to them, No, you must read the entire series because J.K. Rowling's big strength is her complex plotting across all seven novels. But of course the first book doesn't have a complex plot--it's quite simple. People who read it and stop can never understand why someone like me--an adult with a fancy-pants literature degree--is so impressed by that series.

Or take Trang. What do people compliment? The characters. What do people complain about? The fact that it takes a while to get to the "action." Except that the "action" in that book is the character arc--it's not really a book about aliens and portals; it's a character-driven story about a man who is undergoing a significant life crisis. Philippe Trang freaking out at a party on Earth is actually really important to the story--just not the story about space aliens.

So, should I not write sci-fi? Maybe not--it's hard to know. Which is kind of my point....

Emotional continuity

I finished reading Wool last night, and before I launch into my complaints, I'm going to note that it's a very good book--very good. I liked it a lot. (This will be important later: I also like Christopher Moore a lot.)

Buuut...there are issues with it that are similar to the issues a beta reader flagged in an early draft of Trust: The reader is set up to care about certain things that get forgotten. (This post is going to get spoilery about Wool and some of Christopher Moore's books, so look away if you don't like that sort of thing.)

In the course of Wool the main character stumbles upon a group of very isolated, very helpless individuals who are clearly not going to do well without outside assistance. The main character is quite rightfully very worried about these people and makes efforts to help them, efforts that for one reason and another aren't successful the first time she tries them.

And then she leaves them.

You know--leaves them flat. Thinks to herself, God, these people are screwed! and goes on her merry way. Smell ya later!

At the very end of the book, when the main character emerges triumphant from her labors, she decides to reach out to someone who she has neglected--no, not the people she abandoned and could help now, but her father, who the reader has spent very little time with and who obviously has Asperger's and doesn't give a shit about his kid anyway. His survival is in no way threatened, of course.

Honestly--all it would have taken was a sentence to fix this. One sentence. By the end of the book, the main character is in a position to really help people--and she has great plans to help...her own people. Not those other people. They're gross. She doesn't even think about them.

It's a frustrating choice, and I think it goes to show how hard it is as a writer to recognize what you've set the reader up to care about. It can take months or years to write something that it takes mere hours or days to read, and that disconnect between the writer's experience and the reader's experience can be a tough one to bridge. It's also obvious in Wool that Hugh Howey wants the main character's relationship with her father to be A Major Theme--every 300 pages or so we get another little reminder that She Is Estranged From Her Father And That Is Very Bad (Although Her Father Doesn't Care In The Least, So I Am Skeptical About How Meaningful Any Reconciliation Can Possibly Be).

Anyway, it reminded me of a post I wrote on my old blog back in 2007 when I started reading Christopher Moore's books. I started with Bloodsucking Fiends, which I believe was his first book. I've pretty much read them all that this point, and although his books are really funny and entertaining, the very best you can expect from his endings are that the book will just lurch to a halt.

Here's the old post:

Ending well

And then a friend gave me Moore's Practical Demonkeeping and Fluke for Christmas. I just finished reading Practical Demonkeeping, and it is much better than Bloodsucking Fiends--it's just a lot tighter, and there's less of a sense that we're constantly going out of our way because Uncle Chris thinks there might be a joke over here and he'd like to root around for a bit to find it.

But it doesn't end well. It doesn't end horribly--it's not like the narrator wakes up and it was all a dream or anything like that. The plot winds up in an appropriate manner. It's not even as bad as the ending of Memoirs of a Geisha--I'd still heartily recommend this book, while that book is so very good up until the dreadful, forced, Harlequin-romance ending that I never quite know what to tell people.

But the ending of Practical Demonkeeping isn't as satisfying as it could be, and the reason is that Moore spends a lot of time in the book establishing a major romance, which then comes to naught. As in, the two characters involved in the major romance not only don't wind up together, they each wind up with another person. They both had previous relationships with the people they end up with, but in one case the relationship was brief and took place 70 years before the story begins, and in the other the relationship has fallen completely apart, and we only ever see those two interact when they fail to communicate over the phone. In addition, another random man and woman who we have never seen together suddenly become a couple at the end. All these couples live happily ever after, which is nice for them, but...why should I care?

It just feels contrived, like Moore thought it would be neat if the couples ended up in Configuration A, and for some reason he didn't think it would bother the reader if the entire novel was spent setting up Configuration T. The disconnect between character and action is so bad [this part is REALLY spoilery, you should probably skip it if you haven't read the book] that when a character loses her spouse of some 70 years who she genuinely loves and who loves her, she weeps about it for about two minutes, and then she hooks up with some other guy. Way to go, lady! No need to let your husband's violent death interfere with your getting laid!